History

In 1872 Deutsche Bank sets up its business in the United States of America

For more than 140 years Deutsche Bank has had business in the US – a long common history with its ups and downs. Financing the famous US railways is a prime example of Deutsche Bank's early participations in North America.

A management team without experience of business abroad was hardly conceivable for a bank whose purpose, written into its articles of association, was to promote German foreign trade. Georg von Siemens, the first Spokesman of the Board of Managing Directors of Deutsche Bank, and his colleague Hermann Wallich had experience of foreign business, albeit not in North America. Another member of the Board of Managing Directors of the early days, who did not stay for long in the somber offices in Französische Strasse in Berlin, was a German-American: Wilhelm Platenius, whose knowledge of business in New York was to be of use to the bank.

But the bank's first attempts to gain a footing on the American continents were not born under a lucky star. Deutsche Bank acquired takes in the German-Belgian La Plata Bank with operations in South America and in the newly founded private bank Knoblauch & Lichtenstein in New York already in 1872. As overseas business offices, the two companies brought more trouble than satisfaction. They were liquidated in the 1880s.

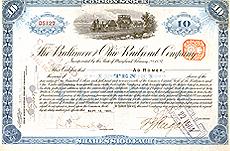

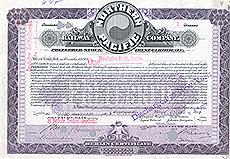

That was during a period in which Deutsche Bank had already developed a strong interest in business in North American railway equities, an involvement that was to play an influential role in its activities in the United States until the First World War. American railway securities had already become popular in Germany starting in the middle of the 19th century - among both investors and speculators. The selection was gigantic, but sometimes the risk as well.

Deutsche Bank came into close contact with the dazzling railway tycoon Henry Villard. He came from Germany and had worked his way up from modest circumstances to the top of several railway companies.

He invited Siemens to the USA in 1883 and it was a veritable expedition corps that set out from Bremerhaven to celebrate the completion of the Northern Pacific Railway in the west of the USA in virtually Byzantine proportions together with Villard. However, it was in this excess that the fall had already been laid.

Siemens saw the risks clearly enough, but had gained a positive impression of the company's development potential. He backed Deutsche Bank's participation in the Northern Pacific. Thus, the year 1883 marked the beginning of Deutsche Bank's North American syndicate business that stretched over the following three decades.

Of course, the Northern Pacific did not remain the only railway in which Deutsche Bank had a stake or with which it maintained business relationships, but it was the one that caused the most concerns for the Board of Managing Directors. Again and again, it came into difficulties because it invested more than it could finance. The risks of the involvement were already clearly foreseeable when Deutsche Bank initiated the foundation of the Deutsch-Amerikanische Treuhand-Gesellschaft in 1890. It was, as the bank's annual report formulated, "to become a concentration point around which European owners of American stocks and bonds could group when it came to legal and financial representation of their ownership rights as part of regular business or in emergency situations".

Just such an emergency situation occurred in 1893: the Northern Pacific became insolvent. In the interests of the German investors, Siemens saw himself with no other choice but to personally arrange for the bail out. With the help of an international syndicate, the company was placed on a solid financial basis.

It came to a fallout with Villard, who had personally not risked or lost anything: »The thing I feel most sorry about for you in the collapse of the Northern Pacific is that you have remained a rich man,« wrote Siemens acrimoniously, unusual for him.

It was the high-profile banker and industrialist Edward D. Adams that Deutsche Bank was able to win over to become Chairman of the Reorganization Committee for the Northern Pacific, and he was also to guard the bank's interests over the next 20 years until the First World War.

The bank did not have its own branch in the United States at this time. There were considerations in 1914 of opening a branch in New York to compensate for the loss of London as a business center caused by the First World War, but these never came to the final stages of planning.

Railways were, of course, the most important but not the only sector in which Deutsche Bank had commitments in North America. The list of syndicate transactions also included the electric industry, machinery construction and mining industry; prominent areas of business. The companies with which the bank maintained business relationships included Edison General Electric Company, Allis Chalmers (farming machinery), American Telephone & Telegraph Company, Anaconda Copper Mining Company, International Paper, Lackawanna Steel, Lehigh Coke, Niagara Falls Power Company, Standard Oil Company of New York and Westinghouse.

With the end of the First World War, the bank's business in the United States changed fundamentally. The flourishing movement of capital during the prewar period was a thing of the past. Germany was now the largest debtor, the United States the largest creditor nation in the world.

Deutsche Bank was hesitant in restoring its American business relationships and regaining its position in the United States. Nonetheless, there was a representative office in New York until the late 1930s. An important activity of the bank was in working for the release of the German assets confiscated during the war. Numerous U.S. activities in the twenties were dedicated to settling prewar commitments. New business was rare, and when it did take place, the roles were reversed: in 1927, the bank took out a bond in the U.S.A. totaling 25 million dollars. With the global economic crisis, Deutsche Bank's foreign business increasingly lost in importance. The dramatic collapse of world trade and a protectionist economy meant that economic relationships abroad became less and less important. The Second World War destroyed the bank's business relationships with the United States.

After the war, the bank refrained from establishing its own foreign operations. Business abroad was conducted primarily through relationships to correspondent banks and supported by a few representative offices and shareholdings. The EBIC, a group of European banks, was also committed to the correspondent bank principle, and it established - with the participation of Deutsche Bank - the European-American Banking Corporation and the European-American Bank & Trust Company in New York in 1968. They offered their services primarily to European companies with business activities in the United States and gave financing assistance to American branches of European companies. In 1974, Franklin National Bank, which had become insolvent, was taken over, which opened the door to retail banking. But in 1988 Deutsche Bank discontinued its involvement with the company.

In addition, the UBS-DB Corporation was established in 1971 and engaged not only in the custody and issuing business, but also in leasing transactions and the referral of shareholdings. Its name was changed to Atlantic Capital Corporation. In 1985 it developed into Deutsche Bank Capital Corporation.

It was first in 1979 that Deutsche Bank opened a New York branch. Deutsche Bank was thus the last of the big German banks to open a branch under its own name in Manhattan. The reason for this long delay was that it had actually been present in the form of its shareholding companies.

As Deutsche Bank increasingly turned to investment banking in the 1990s, its North American business was restructured again and again.

Important intermediary steps were Deutsche Bank North America Holding in 1991 and the organization of Deutsche Morgan Grenfell in 1995. However, it became clear that the bank would not be able to achieve the size necessary for this line of business through organic growth. Deutsche Bank thus began to look for an American bank it could combine with, found the New York-based Bankers Trust, and acquired it in 1999 old-style bankers.

It came to Deutsche Bank together with Baltimore's traditional bank Alex. Brown, which Bankers Trust had taken over two years before.

Following the Bankers Trust transaction, the bank's business reached a new dimension in the region. Its importance was also highlighted by the bank's listing on the New York Stock Exchange in 2001. In the same year, the bank acquired a new office building in southern Manhattan and moved into it, step by step, over the next two years.

Deutsche Bank officially opens its new Americas headquarters at 1 Columbus Circle. The former Time Warner Center is officially rebranded Deutsche Bank Center.